In the apparent run up to war with Iran, President Bush brings into the de facto anti-Iranian alliance India, the superpower of Southwest Asia. India is a nation of over one billion people already with a pro-American tilt and many business dealings with the USA. English is widely spoken by over 100 million people in India and is the USA the number one immgration destination of ambitious Indians.

In the apparent run up to war with Iran, President Bush brings into the de facto anti-Iranian alliance India, the superpower of Southwest Asia. India is a nation of over one billion people already with a pro-American tilt and many business dealings with the USA. English is widely spoken by over 100 million people in India and is the USA the number one immgration destination of ambitious Indians.So let's welcome India as the newest member of the Anglosphere.

Passage to Freedom

The Bush visit to India heralds a new democratic alliance.

Saturday, March 4, 2006 12:01 a.m. EST

Critics of the Bush Administration often lament that its policies have alienated America's traditional allies and embittered just about everyone else. Everyone except, apparently, a billion or so Indians. That's one lesson to draw from President Bush's visit this week to the Subcontinent, which also included stops in Kabul and Islamabad. Relations between India and the U.S. have improved steadily since Rajiv Gandhi took over from his assassinated mother, the repressive and inveterately anti-American Indira Gandhi, in 1984.

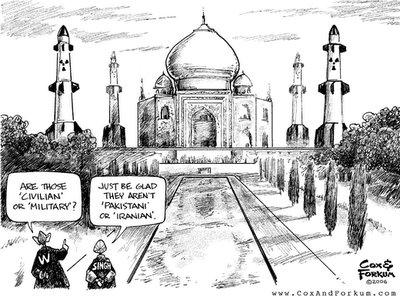

But it's only with this Administration (which early on lifted Clinton-era sanctions on India) that the relationship has matured into a genuine strategic alliance based on shared interests in democracy, globalization and the war on terror. "We have made history today," said Prime Minister Manmohan Singh of the visit, and we can only hope he's right. The most visible marker of this alliance is the deal in which the U.S. would sell civil nuclear technology to India. In exchange, India--a nuclear-weapons state and never a signatory of the 1970 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT)--has agreed to open 14 of its 22 existing nuclear reactors to international inspections.

The remaining reactors could be used for military purposes, including presumably to enlarge and modernize India's modest nuclear arsenal. The agreement's details deserve more extended comment on another day, especially because they must be approved by Congress and the 44 member states of the Nuclear Supplier Group. But one thing is clear: The concerns posed by the agreement have little to do with the uses to which India puts the technology. India is a liberal democracy and a responsible power; it is nonsensical to argue that the U.S. is guilty of "hypocrisy" by providing nuclear technology to India while denying it to rogue states such as Iran and North Korea.

The deeper question, however, is whether the world is prepared to also allow democracies such as Indonesia, Argentina or Taiwan to acquire nuclear weapons. Color us skeptical. Still, there is no turning back India's nuclear-power status. Nor would it have been smart for the Administration to deny India's fast-growing economy an American source of energy supplies when one alternative would be a gas pipeline linking New Delhi with Iran. The U.S. is India's largest trading and investment partner; U.S. merchandise exports to India have more than doubled since 2001, and vice versa. This is a relationship that could blossom by removing every trade and regulatory barrier to it. From the U.S. side, that means removing tariffs on Indian textiles, which can run as high as 29%, as well as U.S. restrictions on Indian agricultural produce. As a protected economy emerging slowly from its socialist past, India has even more to do: dramatically lower import tariffs, which average 20% and often go much higher on items like Scotch whiskey; remove all restrictions on joint ventures and foreign investment in agriculture, real estate and retail; remove set-asides for small businesses; liberalize the banking sector and remove caps on foreign investment in local banks, and create more flexible labor laws. Government approval should not be required for firing workers in companies with more than 100 employees.

We should confess here to having our own corporate stake in reform, and in many ways our experience in India illustrates that the country still has a long way to go to realize its full growth potential. For some time Dow Jones, the parent company of this newspaper, has been interested in publishing an Indian edition of The Wall Street Journal, either as a stand-alone product akin to our European and Asian editions, or in partnership with an Indian newspaper. Until 2002, foreign investment in Indian news and current-affairs publications was forbidden. Yet the current, "liberalized" regime is hardly better. Foreign ownership is capped at 26%, while the principal "local" partner must own at least 51% of the paid-up capital. Foreign publishers are allowed to print what's known as a "facsimile" edition of their newspapers in India, but those editions can include only limited local content and no local advertising, all but guaranteeing their unprofitability.

In addition, government regulations require that three-quarters of directors and all key business and editorial staff would have to be resident Indians. These Byzantine regulations have so far dissuaded Dow Jones from expanding its footprint in India, and we are sure we're not the only company to have figured likewise. That's a pity for us, but we think it's an even bigger pity for Indian readers whose tastes in news and analysis might just be as globalized as the economy in which they are increasingly prospering. Let's hope that in the months and years ahead, the agreements forged this week will help India further shed its socialist past and open new opportunities for everyone.

Related articles:

No comments:

Post a Comment